Anca Bucur

The monster: ma semblable, ma sœur

In 2014, Pierre Huyghe released a film of uncanny images entitled Human Mask, in which the surrounding exteriors, depicting a deserted and shattered town, were shot in a post-Fukushima exclusion zone, with a camera attached to a drone. The main character, a bizarre creature, wearing a Noh mask, is shown wandering in an abandoned shelter, replicating factitious human gestures and repeatedly touching its long dark hair with its thin, claw fingers. The lights are dim, but the shapes are even dimmer, fading in troubled dingy settings. It is by bearing in mind the figure of this disturbingly hybrid, monstrous creature – half animal, half cyborg, half ape, half machine – that I intend to partly unfold the breach between species and to bring in kindred encounters their materiality, conjuring bios and zoe in surfacing the monster and in phrasing the lifeform. While cultural representations of the future usually envision, in terms of automation, the exchangeable chemical bond between humanity and cybernetics, the animal remains secluded – an uncharted territory – still described as the outermost edge of the human. The XIXcentury may have – through its ideology – fostered, perpetuated and advocated for human exceptionalism, indulging it with abstract privileges – language, rationality, consciousness or even subjectivity – in detriment of and in opposition to affectionate materiality, but contemporary capitalism is urging even further the gears of abstraction by implicitly sharpening these privileges not only as constructed inherited traits but also as mandatory features. Modernity engineered the pedestal by carving a white cleansed profile into the depletion of its own history, but contemporaneity lives with the reinforced long-drawn cast of this pedestal beaming light and flashes in the Copernican sun. From this point of view, stripped down in accelerative commodification, the non-human animal is furtherly exposed to exclusion, sentenced to carelessness, and dispossessed of its own nature. Even when narratives about possible, preferable futures are abundant, their storylines are frequently twisting around anthropocentricity, rather than the otherwise around. Movie franchises and marketable publications with their indulged vocabularies and their rather naïve imaginaries, with their augmented image of the victorious hero/ine and their disciplinarian morality fighting the wicked alien otherness are prevailing scenarios in front of those emancipating the species frontier and hybridization in envisioning pan-communitarian ecosystems: the world as intrinsically monstrous.

Tod Browning, Freaks, 1932

Alex Garland, Annihilation, 2018

However, since more and more voices are coming back to Darwin, echoing him in different approaches, “we are less inclined to stress out the links to the divine and more likely to acknowledge animals as our kin.” (Christoph Cox, 2016: 115) The (hu)man is bound to turn a blind eye not only to his companion other, but also to his own nature, both matter and ontology, and along these lines to the persistent definition of life as a hierarchically stratified animated arborescence. Conceptually relying on Aristotle’s ladder (Scala Naturae), depictions of life are replicating a vertical gradient organization from the simplest to the most complex organisms. The Haeckelian tree, Lamark’s descendance tableaus, and even Darwin’s iconic tree of evolutionary relationships are positing a rather linear movement in understanding evolution and are still haunting (not only) the biological conceptualizations of life. An overturning of their hegemony is almost impossible, since the vigor of their arborescent metaphor is rooted in our lexicon, but maybe producing a drift into the obituaries of this inherited tree-thinking is more likely to infer. Nursing the forecourts of this thinking towards the ramifications of branches and roots unfetters a desire for alliance and kinship, sometimes abstracted as what cladists call family-tree: tangled roots and mingled branches are blending to let the forest grow and the single trunk bud.

In On the origin of species, Darwin posits the elimination of boundaries and hierarchies as one of the prime prerequisites in theorizing evolution. If species may (statistically) combine in countless shapes and manifestations, that is due to the fact that the evolutionary process is conceived as a series of variations and mutations through which the other is re-produced and brought into appearance. Evolution is “a descent with modification,” it follows “the play of repetition and difference” (Elisabeth Grosz, 2005: 19), designating a mechanism grounded on mutant recursive replication. The greater the germination, the more the variation is able to enact new monstrous forms of life, especially when “monstrosities cannot be separated by any clear line of distinction from slither variations.” (Charles Darwin, chap. I). Every sprout, embryo or larva is an instance of species mutability, every cell, trunk or molecular chain’s bifurcation represents an open-ended becoming. The difference between species wears the evidence of degree, and not that of kind. In The Descent of Man,the alleged absence of higher faculties in other non-human animals is debunked when confronted with questions of gradation and tendency. The dismantling of human icon happens not by the power of disinvestment, but by that of genealogy: both of its psychological and cognitive faculties are realized as commonly intrinsic and acknowledge as (yet unactualized) tendencies to other species. The intervals of difference among them fail along a material continuum, which is itself the outcome of mingled evolutionary forces. The tree metaphor tunnels its meaning, spreading stems either towards the knotted branches or towards the entangled roots, always in an attempt to forgather a forest and to open the single-trunk cluster to assemblies.

The non-human animal is not only the absolute alterity, “the wholly other they call animal” (Jacques Derrida, 2008: 11) or an anthropomorphized machine unable to recognize itself, yet trough which, like in an optical device, the human animal should be able to foresee itself (Giorgio Agamben, 2004: 26), but foremost, as its human kin, an indeterminate lifeform, snaked by western liberal history of its own agential potentiality. For, rather than defining an essentialist, teleological and finite unit within nature, each living organism designates an ongoing actualization of a virtual field of possibilities. The notion of lifeform is by its own nature plural, already a multiplicity of forms, whether they are actual or actualizable, real or virtual, extant or extinct. They respond and comply with representational contingencies, depicting figurations of ideologized constructions, as well as they rejoin the undetermined chain of nature, portraying evolutionary possibilities. However, it is not only morphology – as a comprehensive compendium of forms, shapes and sizes – which is inherent to our understanding of lifeforms and which is bind to a conception of life as afforded by logic and language within which the field of possibilities is the product of rational imagination, but also materiality stands as central to the notion of lifeform. A morphology which is already material or a materiality which is already morphological, being incidentally agential in its vital emergence and evolution – this is what lifeform terms. Life is therefore embedded in its materiality, building upon its discursivity, but beyond the human-centric catalogue dictating as primordial the linguistic and rational formulation of form and formal reproductions. Instead, through its vitality, life motions towards acknowledging the material-discursive apparatus that enlivens the proliferation of constant morphological variations.

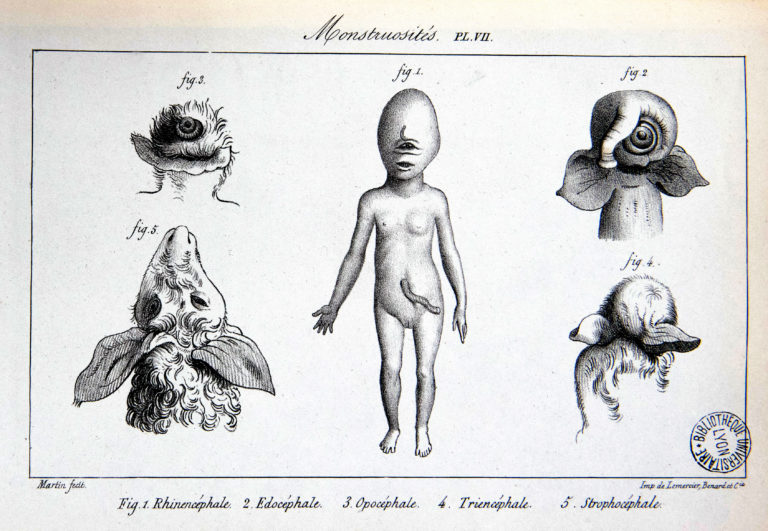

Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Isidore, Histoire générale et particulière des anomalies, 1837

The nineteenth-century French biologists Etienne and Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, along with Camille Dareste, who founded the science of teratology (the study of monsters) annulated the opposition between ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ creatures by refusing to standardize one unique variation of the unlimited string of variability an organism can undertake. “It is impossible”, Dareste wrote, “to establish in any definitive way the limits of the possible.” (Camile Dareste, 2016: 120) Instead of following the path of identical replications, the algorithms of natural selection operate on infinite data, culling from and crossing incentive, simulative and mutable species. The monstrous, mutant creature is a morphological actualization, no different than, the same and on par with any other, of the vast continuum which is matter. Lifeform is subjected to its own potentiality: a realization of transversal connections co-produced in its own embodiment. While this trouble to schedule and predict the dynamics of the evolutionary lines of flight is exposed as situated in teratology, it nevertheless exceeds this territory and sharpens in the era of bio-technological capitalism. Not only does the imperialistic paring of technology and science continue to determine an ever-growing development of computer-based automated devices capable of parsing and manipulating the DNA structures of living organisms, but it also keeps on giving rise to a number of lab experiments, generating cellular and genomes’ intersections, cross-bread lifeforms and genetically modified organisms. All these ascending accelerative advances in both bio- and nanotechnology and in genetic engineering may indeed lead the way towards a potential discharge of the material body, resolving it to a set of flickering signifiers running on a computer screen (Katherine Hayles, 1999: xiv) or to a sort of archives of data (Catherine Waldby, 2000: 6), facing the emergence of digital ontology, but more than ever they give birth to an indeterminacy of inter-associations among species whilst consolidating forms of biopower surveillance and restrictively taxonomizing the vitality of matter. In a naturecultural world, where the ecstasy of techno-scientism feeds on the commodification of life and on the tinkered fantasies of morphogenetics, both ethics and politics integrate each other and conflate in biopolitics by finding means of imposing control on the ethos of transversal potentiality of matter and every so often mimicking the process of sympoiesis. Still, despite the commodity-control system that entails every lifeform, life cannot be reduced to an idiosyncratic ordering of genomic information and marked down to technologically and scientifically enabled mechanistic process. It, besides all, unlocks the interconnected permeability of differences and cracks open the path to contamination, appointing the combinatorial possibilities not only as mere variations but especially as monstrous becomings. Matter’s generative force of self-organization resides in its vital impetus of collaboration, which means working across difference, which leads to contamination” (Anna Tsing, 2015: 29); without it, stagnation – leading to extinction – lies ahead in dusky somber colors, brushing the industrial ruined landscape of the future. Relational contamination rather than exhibiting stasis, activates the vectors of change and germinates new lifeforms, enacting co-production and actualizing the ever alleged and abhorred surplus of in-betweenness. It is by re-tailoring our looks towards the etymological detail that the monster rejuvenates as an already intermediated lifeform, delineating “the in between, the mixed, the ambivalent as implied in the ancient Greek root of the word monsters, teras, which means both horrible and wonderful, object of aberration and adoration.” (Rosi Braidotti, 1994: 77). Exoticized and fetishized as it is by the always sanitized anthropomorphizing (hu)man-centric perspective, the monster turns not into the “wholly other”, but, furtherly, into the “wholly altered other.” Its pinned alteration is rendered complicit with alienness while its own nature is unnaturalized by the colonial normative gaze. In a landscape where the grasping of nature is prescriptive to the rise of European colonialism and willed by the Enlightenment principles of Cartesian dualism, the monster is fundamentally perceived from the point of view of its morphology and reduced to a question of (mal)formation. The formal lens parades a hegemony of anthropocentric representations through which the primacy of form meets the cognitive sovereignty separating intellect from affect and form from matter, entailing a crystallization of the organic and, consequently, of life. Yet, the violence of these epistemologies cannot obliterate neither the agential vitality, nor the intelligent self-organization that are immanent to matter. In this context, the monster is indeed an actualization of in-betweenness, but isn’t this ambivalent in-betweenness also immanent to matter, stating once more the growing complexity of life and its ceaseless impetus to decenter the anthropos and to drop the hierarchical ladder? Isn’t the monster signalizing the limitations of reading life through the rather voyeuristic spectacles of bios, and urging us to revise our own understanding of zoë?

*

The distinction between bios and zoë – although both descending from a common etymological root – can be traced to the faded times of antiquity and translated into the western biopolitical opposition between political and non-political life. While narratives of indigenous cosmologies dissolve this division into multi-perspectivism, defining life as a pluriverse of agents, this separation springs even widely when in connection with the sovereign thought and power. It functions by structuring a critical accurate cut between lifeforms with the privilege of legal rights that offer them a qualified life and lifeforms – humans included – with no legal statue, ratifying them as la vita nuda (Giorgio Agamben, 1998: 4). Bios precludes the “vital materiality that flows through and around us” (Jane Bennet, 2010: x), enunciating it as arbitrary to the parsimonies of social reproduction guarded by the law, and supervised by the (corporate) state. It is therefore this immanent potentiality that zoë in its unexclusive inclusiveness bends open in order to empower agency to matter, indulging lifeforms in transversal connections and self-assemblies of collaborative contaminated aggregations beyond and against the inherent eco-economics and politics of speciesism so predictably praised by bios. Zoë validates non-human agencies and confirms in-betweenness as a commonly shared force particular to all lifeforms, whether it designates a tendency or an actualization. It rejects the dialectical idea of negative difference and urges the need for a zoë-centered egalitarianism to unfold as “a materialist, secular, grounded and unsentimental response to the opportunistic trans-species commodification of Life that is the logic of advanced capitalism” (Rosi Braidotti, 2013: 22) and as a communitarian world that continuously varies by coming into being. Within this logic, the monster prompts not only a critical revisal of biopolitics, but also a re-envisioning of bare life, and slithers even further the always already thin line of separation among lifeforms, restoring overtly porous their frontiers.

*

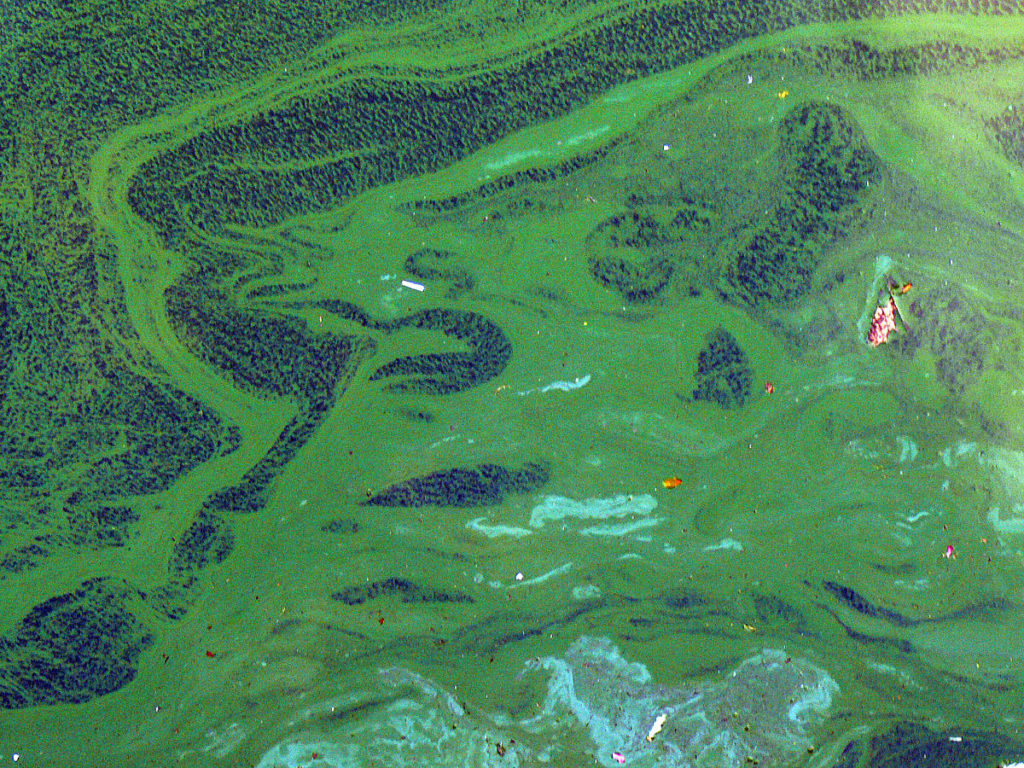

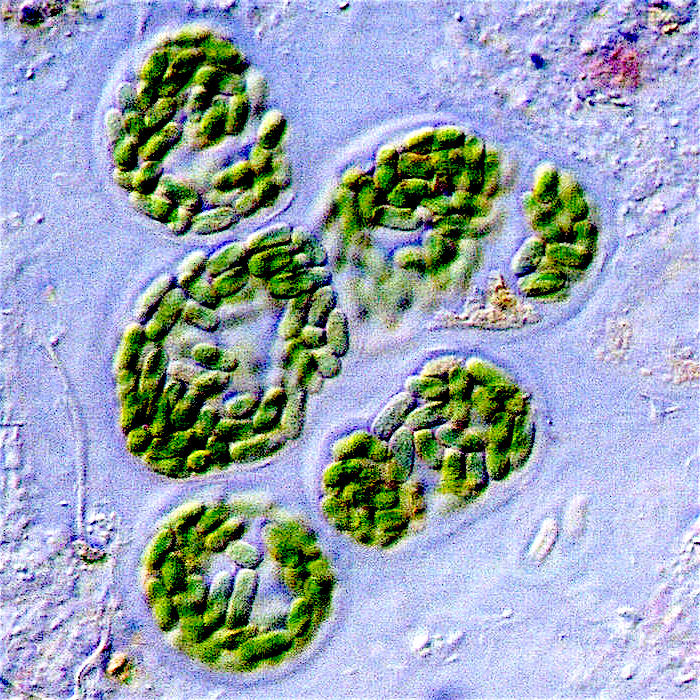

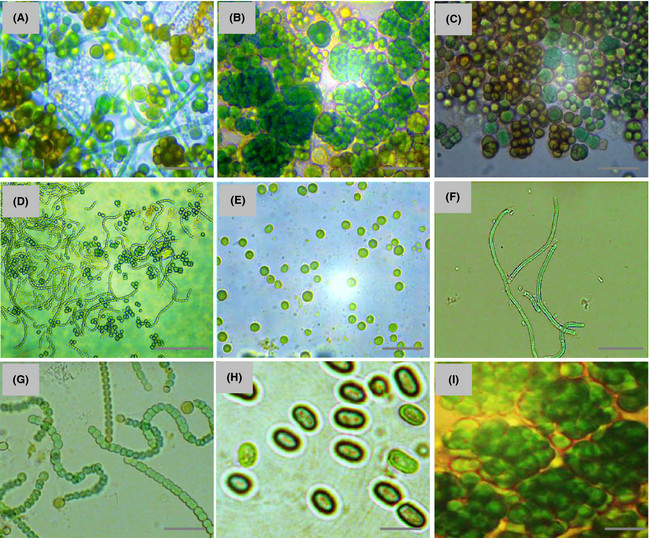

Cyanobacteria are photosynthetic prokaryotic lifeforms, which, although unicellular, frequently grow motile filaments of cells, called hormogonia, to travel away from the main biomass to bud and aggregate into rich bluish-verdant colonies, similar with their phycocyanin pigment used to capture light. Emerging in almost any terrestrial and aquatic habitats, from damp soils, moistened rocks to freshwater, marine or dessert environments, either as a singular composite or in a transversal relationship with plants, lichens or fungi, cyanobacteria are ancestral to green chloroplasts of plants and the brown plastids of algae. Their geological existence is dated more than 3,5 billion years ago, when they widespread into iridescent symbiosis, mutating and causing the biggest chemical change in the planetary history – otherwise known as the Great Oxygenation Event – converting the oxygen-poor atmosphere into an oxidizing one. They evolved to multiply and proliferate, self-assembling and self-organizing, bursting into multifarious morphologies and mediating in-betweenness through their unique capacity to enter multi-species alliances and “to form symbiotic associations with a remarkable range of eukaryotic hosts including plants, fungi, sponges and protists.” (Brian Whitton & Malcolm Potts, 2002: 523). Cyanobacteria are ancient monsters, photoautotrophic teras that, through their vital metabolic force and symbiotic variation, manufactured the current conditions of life on earth and mediated the very actualization of in-betweenness. While being in a continuous state of mutation when collaboratively contaminate/interact with marine and terrestrial plants and animals, they simultaneously naturally reformulate as monstrous lifeforms. Not only metabolic reliance, that is the potentiality of their vitality, is reciprocal, but also their materiality originates mutual and gradual morphologies. The assembly, that is cyanobacteria, self-organizes as assembly anew, differently, and again, continuously. Far-more-than-human, the cyanobacteria is enabling and enlivening planetary geo-morphological life by life’s own communitarian transversal agential vitality, negotiating its very force of self-organizing and stating the interspecies in-betweenness potentiality of present and future life forms.

Bibliography:

Agamben, Giorgio (1998). Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Agamben, Giorgio (2004). The Open: Man and Animal, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bennet, Jane (2010). Vibrant matter. A political ecology of things, USA: Duke University Press.

Braidotti, Rosi (1999). Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory, NY: Columbia University Press.

Braidotti, Rosi (2013). The Posthuman, Cambridge: Polity.

Cox, Christoph (2016). Of Humans, Animals and Monsters, in Ramos, Filipa (Ed.), Animals. Documents of Contemporary Arts, London/ Massachusetts: Whitechapel Gallery/ The MIT Press, 114-123.

Darwin, Charles, On the Origin of Species, retrieved from http://www.literatureproject.com/origin-species/Origin%20of%20Species%20-%206th%20Edition_2.htm. (Last accessed 4 April, 2020)

Derrida, Jacques (2008). The Animal That Therefore I Am, New York: Fordham University Press.

Grosz, Elisabeth (2005). Time travels. Feminism, Nature, Power, Australia& New Zealand: Allen & Unwin.

Hayles, Katherine (1999). How we became Posthuman? Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics, Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Saint-Hillaire, Etienne, Saint-Hillaire, Isadore & Dareste, Camille, drawn from Cooper, Melinda (2014). Regenerative Medicine:Stem Cells and the Science of Monstrosity and quoted in

Cox, Christoph, Of Humans, Animals and Monsters, op.cit.

Tsing, Anna, (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World. On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Waldby, Catherine (2000). The Visible Human Project: Informatic Bodies and Posthuman Medicine, London: Routledge.

Whitton, Brian, Potts, Malcolm (2002). The Ecology of Cyanobacteria: Their Diversity in Time and Space, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.